The Central Empire, also known as the Middle Empire, was a formidable and enduring absolute monarchy that existed from the Founding Age (80) until recent modern times (2987). Renowned for its complex federal structure, the empire was ruled by a powerful emperor who presided over a coalition of elected and hereditary kings. These kings, who governed various regions of the empire, convened in the Kings' Council, a governing body that balanced centralized imperial authority with regional autonomy.

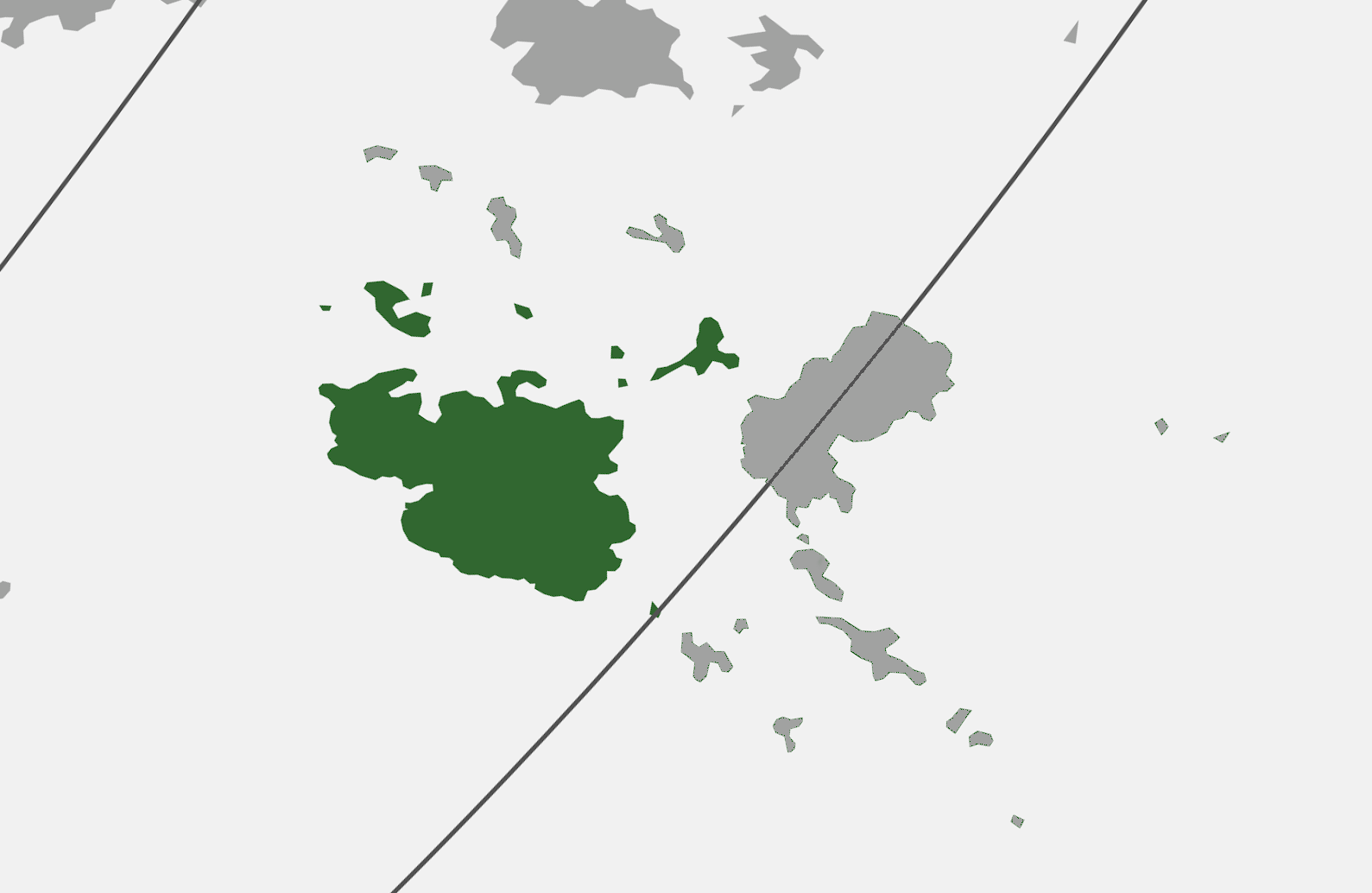

The empire was situated on the largest island of Mangrovia, a strategic and resource-rich landmass at the heart of the Mangrove Region. Over time, the empire expanded its influence, conquering several northern islands and integrating them into its domain. The capital city, Rugutra, was a symbol of imperial power and culture, majestically located on the Foggy Highlands near Írsig Lake. This city served as the political and cultural epicenter of the empire, housing the imperial court and the Kings' Council.

At its zenith, the Central Empire controlled the entirety of the Mangrove Region, establishing itself as a dominant force in the area. However, internal strife and external pressures eventually led to the fragmentation of the empire. The eastern lands seceded during a period of political turbulence, marking the beginning of the empire's gradual decline. The northern islands also broke away but were later reconquered under the assertive rule of the Modern Dynasty, which sought to restore the empire's former glory.

Despite these challenges, the Central Empire's legacy endured through its lasting influence on the region's political structures, culture, and history, making it a central figure in the history of Mangrovia and its surrounding territories.

Name

The name "Middle Kingdom" reflects both the geographical centrality and the cultural self-perception of its inhabitants, who saw their empire as the heart of the world. In their native language, it is called qíri ru-pa̋ngri, which translates to "the eternal realm", underscoring their belief in the empire's enduring significance and its destined permanence in the annals of history. This name embodies the profound sense of pride and identity that shaped the empire's legacy and its people's view of their place in the world.

Government

The Middle Kingdom operates as an absolute monarchy with a unique federal structure that balances centralized power with regional autonomy. At the apex of this system is the Uídaríb, the supreme ruler of the empire, who exercises absolute authority over the entire realm. However, the empire's vast territories are divided into regions governed by subordinate kings or princes, known as the Ududbarű. These regional monarchs, while wielding significant local power, are ultimately subordinate to the Uídaríb.

The northern islands, in particular, maintain their own distinct monarchies, each led by an Ududbarű. Despite their regional authority, these island monarchs and all other regional rulers are bound by allegiance to the Uídaríb and are required to participate in the King's Council, a governing body that serves as an advisory assembly to the Great King. The King's Council is intended to provide counsel and support to the Uídaríb, ensuring that the empire's diverse regions are represented at the highest level of governance.

One of the unique aspects of the Middle Kingdom's government is the method of succession. The Uídaríb possesses the exclusive right to choose his successor, a decision that can ensure continuity or introduce significant shifts in policy and leadership. This method of succession underscores the absolute power of the Uídaríb, who not only commands the present but also shapes the future of the empire through his choice of heir. The combination of absolute monarchy with a federated structure allowed the Middle Kingdom to maintain a delicate balance between centralized control and regional diversity, contributing to its longevity and influence.

Language and Society

The Central Empire is predominantly inhabited by the Ribäng people, who speak the eponymous Ribäng language. This society is intricately organized according to a rigid caste system, which defines not only social hierarchy but also the roles and responsibilities of its members. At the heart of Ribäng society are two particularly powerful and influential castes: the noble caste, traditionally tasked with governance, administration, and religious duties, and the hunter caste, whose members are revered for their skills in both hunting and warfare.

Tension between these two castes is a defining feature of Ribäng society. The noble caste, with its deep-rooted authority and control over the political and spiritual spheres, often finds itself at odds with the hunter caste. The hunters, who are essential to the empire's defense and military prowess, continuously strive to expand their influence and assert their importance in the broader societal structure. This ongoing struggle for power reflects a dynamic and sometimes volatile balance within the empire, as the hunter caste seeks greater recognition and authority, challenging the traditional dominance of the nobility.

Historically, the Middle Kingdom's reach extended to the large eastern island, a territory once firmly under its control. However, this region eventually seceded during a period of internal upheaval, a loss that was partly fueled by the tensions within the Ribäng caste system. The eastern island's separation underscores the underlying societal pressures that have shaped the empire's history and continue to influence its present.

The caste system, while providing structure and stability, also serves as a source of both internal conflict and social mobility within the Ribäng population. As the hunters push for greater influence, the traditional balance of power within the empire is constantly being tested, reflecting the complexities and challenges of maintaining a vast and diverse society under a unified imperial rule.

Provinces

The three northern provinces of the Central Empire hold significant cultural and historical importance, each located on strategic islands off the mainland of Mangrovia. These provinces not only contribute to the empire's rich diversity but also serve as vital centers of power and tradition within the imperial structure.

The Midípsig Islands are particularly revered, as they are home to the sacred grave of Ítmibugwa, a legendary hunter-deity whose legacy deeply influences the local culture. This province is unique within the empire as it maintains its own local monarchy, which governs with a degree of autonomy, reflecting the islands' spiritual significance and their deep-rooted traditions. The Midípsig monarchy is closely intertwined with the religious practices surrounding Ítmibugwa, making this province a pilgrimage destination and a key cultural heartland within the empire.

Pitni Province, situated on Shell Island, stands out as a bustling port republic. Despite its relatively small size, Pitni is a vital economic hub, known for its thriving maritime trade and vibrant mercantile culture. The province operates as a semi-independent republic, with its governance heavily influenced by a powerful merchant caste that has long controlled the region's economic and political affairs. Pitni's strategic location and economic clout make it an indispensable asset to the Central Empire, serving as the gateway to the northern seas and a crucial link in the empire's trade networks.

The Abib Province on the Old Isle holds the distinction of being the oldest and most historically significant region in all of Mangrovia. This ancient province is the cradle of the empire's civilization, where the earliest settlements were established and where the foundations of the Ribäng culture were laid. Abib is governed by a unique dual monarchy, the result of a historic unification of the northern and southern monarchies that once ruled the island separately. This dual monarchy is a symbol of the province's deep historical legacy and its enduring influence within the empire. Abib's rulers are regarded as the custodians of the empire's oldest traditions, and the province itself is often seen as the spiritual and cultural heart of the Central Empire.

Together, these northern provinces form a crucial part of the Central Empire's identity, each contributing its own distinct history, culture, and governance to the rich tapestry of imperial rule. Their unique statuses within the empire reflect the diversity and complexity of the Central Empire's federal structure, where regional autonomy coexists with overarching imperial authority.

Flag

Black symbolizes the formidable power and enduring legacy of the ancient beetle gods, revered throughout history for their might and influence. Orange, on the other hand, is the sacred color of the Ávabuz religion, representing spiritual devotion, enlightenment, and the divine connection between the faithful and their deities. Together, these colors encapsulate the deep reverence for both the ancient and spiritual forces that have shaped the culture and identity of the people.

Motto

The motto of the Central Empire, "Our ancestors and the emperor, forever," encapsulates the profound reverence for both lineage and imperial authority that defines the empire's cultural identity. In the ancient tongue of Old Ribangese, this enduring pledge is expressed as "kwü-kun-dung ag-aq̃adubanra miri ugutra kir," a phrase that resonates deeply with the empire's values of ancestral honor and unwavering loyalty to the emperor, symbolizing the eternal bond between the past and the present in the heart of the nation.

History

Old Dynasty (Pre-0 to 160)

The Old Dynasty marks the beginning of recorded history, with Ítmibugwa as a foundational figure who shaped the island’s culture. This era sees the birth of key figures like Kuǵiraf and the establishment of the Central Empire in 80, which would dominate the political landscape. The Old Dynasty is a period of consolidation, expansion, and the first steps toward empire-building, culminating in a time of relative stability.

Forgotten Era (Dates Unknown)

The Forgotten Era is shrouded in mystery due to the loss of historical records. What is known is that the Old Dynasty fell, and a new ruling line emerged. The lack of clear details leads historians to classify this time as “forgotten,” suggesting a period of upheaval or decline that reset the political landscape before the rise of the next dynasty.

Foreign Dynasty (1220 to 1600)

This era is defined by foreign influence and cultural shifts as elites from the northeast, speaking a different dialect, rise to power in 1220. The Foreign Dynasty oversees the conquest of the entire island by 1336, increased collaboration with external powers like the Milenians, and a golden age of science and invention in the mid-1400s. Religious change follows, with the spread of the Lusoa faith in the northern islands. The empire reaches its greatest territorial extent by 1560, but internal strife due to its vast size leads to growing tensions and resentment toward foreign influence by 1588, setting the stage for a change in leadership.

Noble Dynasty (1600 to 2300)

A coup d'état in 1600 by native nobles from the mountains replaces the foreign rulers, ushering in a new native dynasty. This era sees both triumph and tribulation: parts of the empire secede early on, and the empire faces external threats, such as hostility with the Milenians and defeat in the Mangrove-Movamom War. An invasion from the Kokos-Confederacy leads to the emergence of Ribangese Sea Nomads, settling in the east of the country. Despite these challenges, the empire experiences periods of agricultural reform, spiritual resurgence, and the emergence of new political structures, such as the Ribangese Sea Nomads in 2230. The dynasty ultimately falters due to internal decay and natural disasters, including the 2179 tornado that devastates the capital.

Modern Dynasty (2300 to 2807)

The Modern Dynasty represents a renewed sense of purpose after the Noble Dynasty's decline. Beginning in 2300, it brings reforms, such as the Script Reformation of 2345, and oversees the Reconquest of the northern islands by 2508. However, internal contradictions and growing economic disparities, especially after 2639's Prostitution ban and rise in slavery, lead to instability. By the late 2800s, social tensions are high, setting the stage for future upheaval.

Tyrannical Dynasty (2807 to 2987)

An absolutist ruler takes power in 2807, marking the start of the Tyrannical Dynasty. The period is characterized by authoritarian rule, social unrest, and environmental crises, such as the 2823 famine. While the dynasty witnesses a small Industrial Revolution in 2856, the benefits are not evenly distributed, and separatist movements arise. By 2938, an economic crisis further destabilizes the regime, culminating in the rise of the Rugutra Commune, a radical political movement, which begins the final collapse of imperial rule.

Revolution (2987 to 2993)

The Revolution Era is marked by the dissolution of the Central Empire in 2987. Civil war and secession movements sweep through the former empire, with the northern islands and Shell Island declaring independence by 2988. The west follows suit with its own secession, and the revolutionary forces establish a new republican government in 2993, signaling the formal end of centuries of imperial rule.